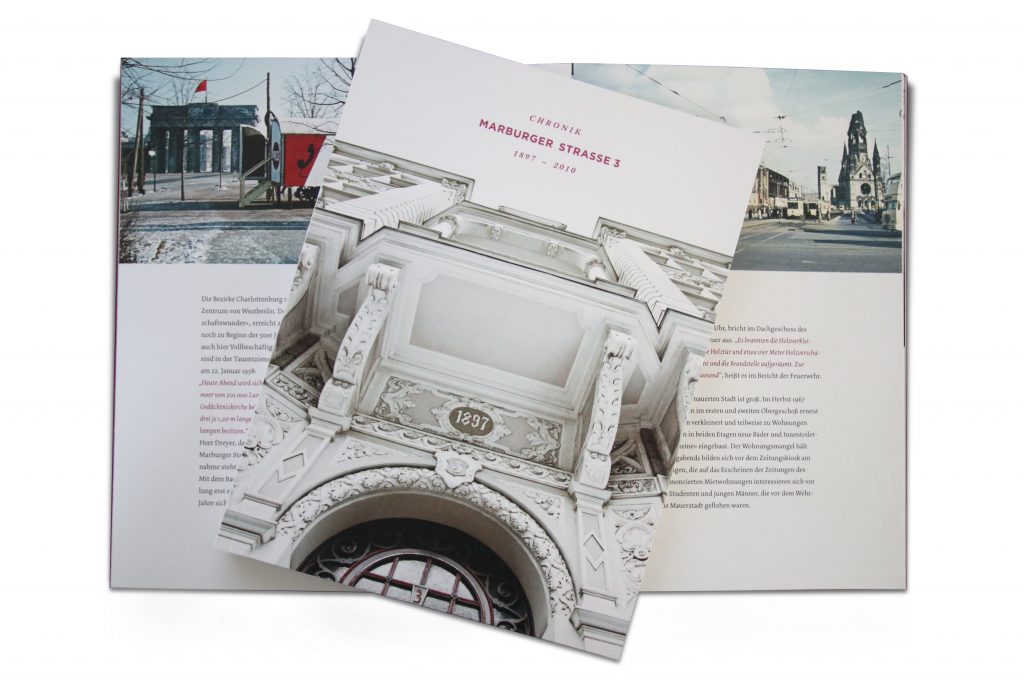

THE CHRONICLE

1896

For a long time Tauentzienstraße managed to stay one step ahead of its rival, the Kurfürstendamm. There was more bustle on the street and more glamour in the neon signs that blazed down from the rooftops. The facades looked almost transparent, aflame with light from top to bottom. Virtually every floor was filled with businesses and offices, places of commerce and labor.“ 1

Tauentzienstraße is Charlottenburg’s original boulevard, whereas the Kurfürstendamm was always more of a ‘sandy embankment’. The town itself is named after Friedrich III’s wife, Sophie Charlotte (1668–1705). Investment in the construction of apartment buildings is considerable, and the population of the district soon grows exponentially. In 1871 the number of residents in Charlottenburg is just 20 000. By 1893 this figure has reached 100 000, and by the turn of the century it has climbed to 182 000 residents. At the beginning of the ‘Golden Twenties’ there are 335 000 people living in the town. The Jewish residents of Berlin are particularly drawn to it. Between 1890 and 1895 the Jewish population of Charlottenburg grows by 219 per cent, while the number of Protestants and Catholics increases by

The end of Tauentzienstraße, not too far from Marburger Straße, is dominated by the Romanesque silhouette of the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church, which is erected in 1895.

The ‘Café Kranzler’ is built at the corner of the Kurfürstendamm and Joachimstaler Straße in the same year. It would later become famous well beyond the city limits of West Berlin, although initially it is just known as ‘the little café’.

1897

The Berlin address directories of 1897 list a new building at Marburger Straße 3. Paul Mühsam and E. Sohn are registered as its owners. The same names are given for the building site at house

number 4.

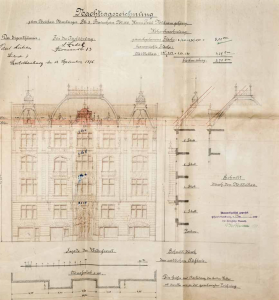

On 6 June 1896 the Royal Police Directorate in Charlottenburg receives a planning application for a new building at Marburger Straße 3. In his letter to the authorities, Paul Mühsam informs them of the following: “I have asked

the builder Herr S. Zadek of Fasanen Straße 13 to deal with the submission of the project and to arrange the necessary permits.” On 16 July 1896 the construction plans are checked by the royal planning authorities. Planning permission is granted in July the same year and the finished structure of the building is inspected as early as November 1897.

A year later, in 1898, the grand brickwork building that has been erected on the neighboring plot is sold to a charity called the ‘Marienstift’ (Mary’s Foundation). Here, the new owner establishes a hospice for young professional women. At the same time, Paul Mühsam becomes the sole proprietor of the building at Marburger Straße 3. The Berlin directories list his profession as “rentier” (a man of private means). The new building with its generous representative apartments is soon filled with life when the first occupants move into the five-story structure. The individual apartments each consist of eight to twelve rooms. The ground floor is set aside for shops and businesses, and the shopkeepers and tradesmen are able to move into the rooms on the mezzanine level. These apartments are occupied by people such as master tailor E. Böhlen and, for a short time, a female artist by the name of E. Gregor. One of the first tenants is Herr Rauhut, who would later become the porter of the building.

Marburger Straße has still not been paved at this stage, yet not a single tree adorns the street. “In line with the enclosed plans, Marburger Straße is soon to be paved over between Tauentzienstraße and Augsburger Straße.” To judge from the files of the Charlottenburg municipal authorities from 16 April 1904, it is still unclear at this point whether any trees are going to be planted on the street. “It seems unlikely that the Berlin Sanitation

Department will agree to the proposed planting of Marburger Straße. According to the agreement of 1889, streets with a width of less than 26.4 m are not supposed to be planted at all.”

1908

In 1908 Paul Mühsam and his wife Johanna Elisabeth (née Hoffmann) have a daughter: Elisabeth Ruth Hildegard. The documents give Chemnitz as her place of birth. A year later the family moves to Marburger Straße. A dozen residents are registered as living in the building, among them a doctor, a florist and a hairdresser. All of the tenants have telephones.

The 20ies

„

“On 16 January 1928 Hildegard Mühsam, born in Chemnitz on 9 April 1908, is registered as proprietor on the basis of Paul Mühsam’s certificate of heirship, dated 18 January 1923.”

Paul Mühsam does not live to see the development of Charlottenburg. He dies on 20 November 1922. According to his testament, the house on Marburger Straße is inherited by his wife, Johanna Elisabeth ‘Else’ Mühsam. Paul Mühsam’s will stipulates that his property is to go to his daughter

Hildegard Mühsam if: “1) the widowed Else Mühsam dies, or 2) marries.”

In the latter case, the daughter would inherit half immediately and the other half after her mother’s death. Else Mühsam does not marry again, but evidently she does sign Marburger Straße over to her daughter Hildegard, for the Land Registry Office confirms this transfer to her daughter on 16 January 1928. As before, though, the Berlin address directories still have Else Mühsam listed as the proprietor and the practical business of running the house is still carried out by the widow.

In June 1925 the attic at Marburger Straße is converted into a painter’s studio. No further changes are made in the twenties. Thirteen tenants are registered as living in the building. From the proprietor’s perspective, the building is well tenanted.

The 30ies

Judging by the Berlin address directories, there was no lack of residents at the house on Marburger Straße. There are thirteen businesses and private individuals listed on the books over the years. Many of the residents have been living in the building since the beginning of the twenties: a doctor and university professor by the name of von Lichtenberg, engineer Kirchner, Commercial Consul Simon and a salesman called Löwenthal, for example.

Nonetheless, Else Mühsam believes the rental market is getting worse, since the demand for large apartments is not high enough.

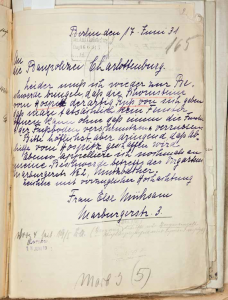

In May 1931 Else Mühsam applies for permission to convert the large, eight to twelve-room apartments into smaller units of five to six rooms. To this end she writes to the municipal planning department on 11 May 1931 in order to obtain the necessary exceptional permissions.

“Since the project contravenes the terms of § 7, item 12, of the building regulations from 9.11.1929, according to which separate side and transverse buildings may not be established beyond a line 20 m from the main front of a building with a street frontage, I hereby request that I might be granted a dispensation for the planned conversion of the twelve-room apartments. My justifications are as follows:

1) The first courtyard is accessible via a passage of the prescribed 2.50 m breadth, the second courtyard via a passage of 1.25 m breadth.

2) The stairwells in the side wings have the required breadth.

3) The unoccupied apartments severely endanger my subsistence and also represent a considerable loss of revenue for the state.

In the expectation of a prompt and favorable decision on this matter, respectfully yours, Else Mühsam”

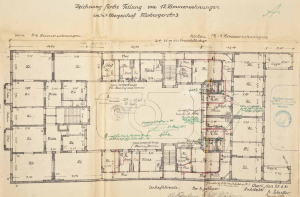

On 10 March 1933 the planning department reaches its decision on Else Mühsam’s application for permission to reduce the size of the apartments. “The applicant intends to partition the large apartments on the second and fifth floors in order to create separate apartments at the rear situated in the transverse building and partly in the two side wings. Given the difficulty of leasing these large apartments and considering the present economic climate, the dispensation is approved.” The relevant permission is granted by the building authorities and stamped on 20 March 1933.

In 1934 Else Mühsam and her daughter Hildegard are clearly experiencing difficulties on account of their property, for on 9 February the National Socialist Commercial Chamber at the Charlottenburg District Courts inform Else Mühsam in writing that the building on Marburger Straße, the property of her daughter Hildegard Oppenheim (née Mühsam), has been transferred back into her name. “The cost value of this piece of

land is calculated at 350 000 marks, the value for tax purposes is 30 700 marks.” Nevertheless, the Berlin address directories for 1935 and 1936 still have the “Mühsam heirs” listed as the owners. Herr Gießbauer, the long-serving caretaker of the building, is replaced by a property agent by the name of Mittelstand, who has offices at Landsberger Straße 7 (NO18). His tenure coincides precisely with the period in which the ownership of the building is evidently being disputed. It is also during these years that the long-term residents disappear and are replaced by businesses and associations with close ties to the National Socialists.

The property relations of the building have evidently been clarified by 1937, for Else Mühsam is now listed as the sole owner in the Berlin address directory. Although legal ownership of Marburger Straße has been transferred back from daughter to mother, the entry on Hildegard Oppenheim’s right to inheritance is still present in the land register.

The year 1937 brings further changes, also with regard to the tenants. There are now numerous businesses in the building, the Association of Agricultural Machine Retailers and the Association of Sewing Machine Retailers.

Almost all the former residents have disappeared. The one exception is J. Kirchner, the engineer who has lived in the building since the early twenties. He now has his own business in the building: the Preparation and Machine Construction Association of the Construction Machine Commerce Group. He wants to expand this company and extend the mansard roof as an office space for it.

Elisabeth Ruth Hildegard Oppenheim (née Mühsam) is paternally half Jewish. Having married the manufacturer and doctor of law Alexander Oppenheim in 1928, they divorce in July 1934. In August that year Hildegard marries the manufacturer Karl Adolf Moritz Israel Ladewig. They divorce in March 1939. Just half a year later she marries the Danish businessman Erik Schmidt. In October 1939 Erik Schmidt travels to Berlin to marry. This is the first time the future couple meet. The purpose of the marriage is clear to both parties from the outset. Hildegard Mühsam wants the Danish citizenship she can automatically claim once they are married. The couple fall in love with one another when they first meet, such that what

was originally planned as a formal arrangement develops into a genuine marriage. The wedding takes place in Berlin on 26 October 1939. Erik Schmidt is officially registered in Berlin from 8 October to 30 October 1939. His address is given as the “Pension Korfu” at Rankestrasse 26. As a result of the marriage Hildegard Schmidt is registered at her husband’s address: Frederiksberg, Danss Plads 10. But in reality Hildegard Schmidt never moves to Denmark.

In November 1939 the couple meet for few days in Copenhagen and again in Berlin in December that year, where they stay in a hotel. Hereafter and until the end of the war the marriage only exists on paper. In all likelihood Hildegard Schmidt evades Nazi persecution as a result of this alliance.

In 1946 Erik Schmidt applies for a divorce from his wife. Hildegard Schmidt retains her Danish citizenship until the end of her life. The divorce is complicated by the fact that the couple do not have a valid marriage certificate. Are the German or Danish courts responsible? The matter is dealt with in Denmark. Hildegard Schmidt is not obliged to pay any compensation for the property she brought to the marriage.

1943

On the night of the first to second of November 1943, Charlottenburg is the target of heavy bombing. The subsequent airstrikes of 22 and 23 November 1943 reduce the district to ash and rubble.

The Berlin property of the Mühsam family survives.

Immediately after Hitler’s seizure of power, both Jewish people and property are put under pressure. Jewish-owned real estate is initially sold at compulsory auctions. From 1940, all remaining real estate automatically becomes the property of the state and is assigned, among others, to the police and the armed forces. Despite the pressure Else Mühsam is presumably subjected to, she and her daughter manage to retain their common property throughout the war.

Did the property at Marburger Straße 3 remain in the possession of its original owners because Else Mühsam was not a Jew and her daughter was protected by the Danish citizenship she acquired through marriage? Or did the property go untouched because Else Mühsam, with the help of caretaker Erich Rossmann, was able to find enough ‘Aryan’ businesses as tenants?

Or were these businesses arbitrarily assigned as tenants by the authorities? One fact that suggests the latter, among others, is that when the engineer Kirchner applied for building permission to extend the mansard as an office, he did so in his own name, without the signature of the building’s owner.

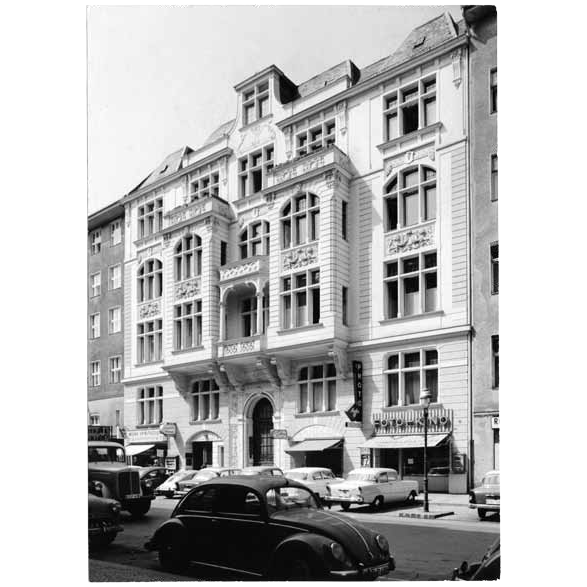

End of war

The buildings on Marburger Straße are almost completely reduced to rubble, with one exception. Number 3 is still standing and looks almost as splendid as it ever did. As though by a miracle, the building itself and even the facade with its stucco ornamentation have survived the bombings unscathed.

As early as the end of 1945, Marburger Straße 3 again gets caught up in the mill of bureaucracy due to ownership issues when Else Mühsam decides to sign the building over to her daughter again. The district of Charlottenburg is in the British-occupied sector and the transfer of property is not possible without the approval of the British.

In June 1947 Else Mühsam submits the following statement in writing: “I the undersigned, Frau Else Mühsam (née Hoffmann) of Berlin W.50, Marburger Straße 3, declare the following under oath to the District Court of Charlottenburg: my estate is not in any way subject to control or confiscation according to the terms of Law No. 52 of the American, British and French Military Government, nor to Command No. 124 of the Soviet Commander

in Chief, nor to any German authority sanctioned by them.” In a letter of 1 November 1947 the District Court of Charlottenburg finally informs Ernst Dahlmann that the building on Marburger Straße belonging to Else Mühsam has been signed over to her daughter Hildegard Schmidt.

1957

At 10 am on 19 January 1957 Johanna Elisabeth ‘Else’ Mühsam dies in her apartment at Marburger Straße 3, one month before her eightieth birthday. Hildegard Schmidt marries Ernst Dahlmann on 10 March 1958. It is her fourth marriage.

The districts of Charlottenburg and Wilmersdorf lie at the center of West Berlin in the now divided city. The economic upturn, the West-German ‘economic miracle’, eventually also reaches Berlin. The mass unemployment that prevailed in the city as late as the beginning of the fifties now recedes, and by 1960 there is full employment even here. The first indications of the economic upturn can be seen on Tauentzienstraße. The newspaper Der Tagesspiegel reports the following on 22 January 1958: “For the first time since the war, Tauentzienstraße will this evening be illuminated by a sea of lights at 201 000 lumen. The thirty-two modern lamps, each of them consisting of three 1.20 m tubes three times as bright as standard incandescent light bulbs, are to be hung at a great height on both sides of the street from

Wittenbergplatz to the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church.” Herr Dreyer, who lives as a tenant in the studio apartment in the attic of the front building at Marburger Straße 3, has a new oil stove installed in his ‘anteroom’. The building authorities raise no objections to it being fired up.

The construction of the Berlin Wall on 13 August 1961 brings economic growth to a temporary halt. The traces of the war remain visible for a long time to come, until the end of the sixties.

1961

At 2.27 pm on Friday 20 January 1961, a fire breaks out in the attic of the left wing at Marburger Straße. “The wooden paneling of the central heating expansion chamber was burned, as were the wooden door and approximately four meters of wooden cladding. The fire was put out with the hand-pump extinguisher and the burnt areas were cleaned up. A stepladder was used. The police were present.” This was the firemen’s report.

Demand for accommodation in the walled city is high. In fall 1967 Hildegard Dahlmann has the apartments on the second and third stories converted again. The large office spaces are made smaller and some of them converted into apartments.

To this end, new bathrooms and internal toilets are built on both floors, “with ventilation via the chimneys”. The housing shortage lasts well into the seventies. On Saturday evenings long lines of people form by the newspaper kiosk at Bahnhof Zoo, waiting for tomorrow’s papers to arrive. Those interested in the apartments advertised to let are primarily students and young men, who are streaming into the walled city to avoid military service in West Germany.

1970

“It was purely interpersonal sympathy; there was no more to it than that. I was about thirty and the lady was about seventy.”

Volker Mayr responds to the advert in writing, and before long Frau Dahlmann gets back in touch, saying that her tenants include a restaurant owner and a university professor, among others, but that she “still doesn’t have a journalist.”

Hildegard Dahlmann receives Volker Mayr “in her incredible apartment on the piano nobile. It was highly entertaining and stimulating to chat with this distinguished elderly lady.”.

She said, you do realize you’ll be living in the apartment where I “spent my childhood.”

Volker Mayr recalls that there were already a number of offices in the building when he moved in; not just in the front building, but also in the side wing. The Berlin Fashion Fair had its offices in the apartment above Volker and Ellen Mayr.

Although selecting tenants is generally the task of the caretaker of a building, Hildegard Dahlmann nevertheless always reserves this right for herself.

And in any case, she is the one who bears responsibility for the building and its maintenance. The facade of the building is repaired several times. The owner makes a point of ensuring that everything is kept neat and tidy. “After many, many years she called us up and said the balcony with the glazing needed renovating because it wasn’t in good order. The renovation of the glass would have cost 16 000 marks. Frau Dahlmann offered to take on half the cost. The tenants would have had to pay the rest. We thought to ourselves, 8000 marks is an awful lot of money.”

Towards the end of the conversation Frau Dahlmann says to her tenants: “Very well, we shall have to tear it all out. Otherwise it will be unsafe.” Hence the large, broad balcony of the side wing has now been unglazed for decades. “And we have to admit, it really is rather nice having it open,” says Volker Mayr, now a pensioner who grows numerous culinary herbs on the balcony, and reads the newspaper and breakfasts with his wife Ellen there whenever the weather permits. When Volker and Ellen Mayr move into Marburger Straße in 1972 the fine wooden floorboards in the apartment are still hidden under carpeting.

“There were carpets that we later ripped out, underneath them a thick layer of linoleum. This linoleum was that beautiful green stuff they had in the post-war era, but it was quite shabby and had started to smell. We decided to tear it all out. There were quite a few layers on top of it, and it all smelled awful, but underneath we found this wonderful flooring from the period around the turn of the century, pitch pine floorboards from America. They’re especially hard and broad and they don’t have knots. You don’t see those so often.”

In the period when the linoleum was laid the Mayrs had rented the apartment out as an office space, to the Klöckner Steel and Metal Company, which had had premises on Marburger Straße before the war.

“Later on I actually met a few people who said, oh, I worked there when I was with Klöckner.”

1984

In the small hours of 30 October 1984 Hildegard Dahlmann dies at the age of 76.

According to the will, the building at Marburger Straße 3 is bequeathed to the long-serving caretaker, Karl-Heinz Wilhelm.

since 2009

When Timo Miettinen first sees the building at Marburger Straße 3 it is, without exaggeration, love at first sight. At the turn of 2009 and 2010 he takes vacation in Berlin and, quite by chance, finds himself standing at the corner of Marburger Straße with his wife, wondering why the name of the street is so familiar to him.

“I said to my wife, let’s take a walk down here. It was then that I saw this incredibly beautiful building for the first time.”

imo Miettinen has been looking for a suitable Berlin property for EM Group, his Finnish family business, for a long time. He has already looked at over forty properties without finding anything that fits the bill. Standing in front of the building at Marburger Straße 3 he recalls having seen the name of the street in the documents from his bank. Perhaps this was the building mentioned in the exposé? The estate agent, currently on a ski- slope somewhere in the Alps, confirms his guess and arranges a viewing for the very start of the new year.

“My wife and I had a look at the building and we were amazed.” This historically significant and ideally located house is exactly what Timo Miettinen had been looking for for so long. After that, everything moves along very quickly. After tough negotiations, the contract with Karl-Heinz Wilhelm is finalized just a few weeks after their first meeting in the summer of 2010. Since that time the ‘piano nobile’ where Hildegard Dahlmann had lived until her death has been completely restored. Having undergone so many changes over the decades, the original atmosphere of this ‘noble

level’ is given a new lease of life. The old wall and ceiling structures that were originally installed for provisional purposes have served their time. The stucco ornamentation on the ceilings is repaired, the original floors that had come to light beneath the carpeting and the linoleum now radiate with a new luster. In repairing the building the new owners want to retain as much of the old as possible, but if new elements do have to be constructed, the architects responsible for the restoration, Wille und Sollich, make it clear that these should be in modern forms.

In terms of function, too, the new owners, Timo Miettinen and his three sisters, strive for a healthy combination of old and new. The aim is to gradually modernize the building and to lease office spaces, but Timo Miettinen also wants to “support culture, design and art.” Part of the piano nobile is being redesigned for this purpose. Timo

Miettinen wants to create an axis between Finland and Germany. “We’re thinking about furnishing an apartment with examples of Finnish and German design. We could then use the rooms in the main area on the second floor to put on various events, or we could rent out the rooms to other businesses for their own events.”

Supporting contemporary art is a heartfelt desire for this passionate art collector. “There are many talented Finnish artists in Berlin that no one knows about yet. These spaces could be used to exhibit Finnish and German art, together or separately.” And Timo Miettinen is not writing off the possibility of showing works from his own collection here at some stage. The Finnish-German connection has been a part of Timo Miettinen’s life since he was twelve. It was then that his father, who founded the electronic accessories firm Ensto Oy in the fifties, sent his eldest son abroad for the first time.

…

“The creative spirit has moved east, but we’re convinced that this district will also develop in future. We want to be part of the success story of creative Charlottenburg.” This is Timo Miettinen’s vision.

author: Irja Wendisch

THE PUBLISHED CHRONICLE

The chronicle can be purchased in our office at Marburger Street 3 for 20€ per piece. The office is open from Mon-Fri between 10 am and 4 pm.